-

Background

The patient, a 16-year-old male, presented in the office to be re-evaluated for catching, locking and intermittent right knee pain. The patient previously sustained an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, which required surgical intervention. The injury was the result of a hyper-extension of the right knee while playing volleyball. The ACL was reconstructed using a RTI™ semitendinosus allograft using an all-inside technique with tightrope and washer fixation. An allograft was selected after confirming a diminutive patella and limited hamstring width on ultrasound. After three months of post-operative care, the patient had maximized rehabilitation and was then released with a home exercise program and graduated return to sport limitations. Approximately six months following the surgery, the patient was braced with no issues. At one year from the index surgery, the patient began to experience pain in the surgically-repaired right knee, leading to a return visit to the office. The pain was associated with a blow to the front of the knee while diving for a volleyball.

-

The Case

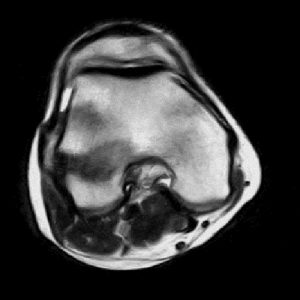

The patient presented in the office with continued pain and intermittent “popping” in his right knee following a recurrent volleyball injury. During physical examination, he displayed Grade II laxity with a Lachman’s test with a solid end-point, suggesting potential ACL deficiency. In addition, a moderately positive anterior drawer test and negative pivot-shift test were exhibited by the patient. Finally, the patient had lateral joint line tenderness. The physician was unable to reproduce the “popping” sensation on exam despite multiple attempts. Based on the findings, the patient was sent for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the right knee. The patient returned for an MRI consultation, where it was determined that the MRI imaging results were inconclusive as to the reason for the patient’s pain. Due to the inconclusive findings, the physician presented the option of performing an in-office diagnostic arthroscopy, using the mi-eye 2™, to determine the patient’s pain generator. The patient and his family consented to the in-office procedure.

The Answer

The patient was positioned on the examination table in a supine position with his right knee hanging off the end. The knee was prepared using a standard aseptic technique to clean the procedural site. The right knee was injected with a local anesthetic of 10cc 1% lidocaine with epinephrine and 0.25% marcaine. The joint was left for 15 minutes to become numb prior to the introduction of the mi-eye 2™ needle. Once the joint was numbed, the needle arthroscopy was introduced into the patient’s knee and a second anesthetic injection of 5cc was given in the joint capsule. A 10cc syringe of sterile saline was attached to the luer port on the needle arthroscopy to assist in clearing the visual field while in the joint. The mi-eye 2™ scope was navigated to visualize the prior ACL repair. While examining the ACL repair, the mi-eye 2™ revealed that the suspension button (“tightrope”) of the ACL graft had failed, resulting in partial slippage of a suture back into the femoral tunnel as the graft healed. The slipped suture caused abrasions to the ACL and the underside of the femoral condyle. The majority of the original ACL graft was stable and well healed. Following the discovery, the physician proceeded examine the rest of the patient’s knee. Further examination revealed a tear of the lateral meniscus, which was not shown on the MRI. Upon completion, the mi-eye 2™ was removed from the patient’s knee and the portal was cleaned and covered.

Based on the mi-eye 2™ findings, it was decided that the patient’s next step is to have an arthroscopy in the operating room to assess ACL graft’s viability. At the same time, the slipped suture would be debrided and the newly discovered lateral meniscus tear would be repaired. The physician was able to reassure the patient’s parents preoperatively that ACL revision reconstruction was unlikely.

Discussion

MRI is a very useful tool in diagnosing conditions of the knee, but also has its limitations. In this case, the MRI did not show the ACL and meniscus pathology that was evident upon utilizing the mi-eye 2™. The mi-eye 2™ allowed for the direct visualization of the patient’s ACL, thus allowing the physician to see the failed repair and slipped suture, which was causing the pain. In addition, the mi-eye 2™ was able to visualize the lateral meniscus pathology previously not suspected. Many times, the findings from the patient’s MRI would have resulted in prescribing physical therapy to treat the pain or a diagnostic arthroscopy in the operating room. Most likely, the prescription of a physical therapy plan would have resulted in continued pain for the patient. Furthermore, a diagnostic arthroscopy would have resulted in an additional unplanned treatment for the patient since the lateral meniscus tear would have been an unexpected pathology.

The use of the mi-eye 2™ saved the patient an unplanned treatment, reassured his parents regarding the severity of the injury, allowed for better surgical preparation by detecting the lateral meniscus tear, as well as allowed for preoperative precertification for treatment.